Are we doing 2018 again?

The backlash to President Trump’s ICE is rapidly altering the political landscape, reshuffling both parties’ calculuses on the issue that did more than any to return the president to the White House. Look no further than the movement sweeping through Democratic governors’ mansions. In the past week, two governors, New York’s Kathy Hochul and New Mexico’s Michelle Lujan Grisham, have announced their support for a statewide ban on 287(g) agreements. A third, Maryland’s Wes Moore, appears likely to sign a similar measure.

The movement of blue state governors against the agreements is noteworthy for both the political and policy implications. As I wrote last week, these agreements are crucial to large-scale deportation: they enlist local police in immigration enforcement, allowing ICE easier access to jails and streamlining apprehension. The more states that ban localities from entering into the agreements, the harder the administration’s task.

Notably, limiting 287(g) agreements was not as much of a focus the last time Trump was in the White House — even as congressional Democrats sprinted left on immigration, governors were more hesitant, with only three states banning the agreements during his first term. When he returned to office last year, the total number of states prohibiting the agreements stood at six.

Now, that number could hit ten just this month, as mainstream Democrats seem to be betting the voters’ wariness of ICE excesses now outweighs other concerns. That comes as the country’s center of gravity has shifted, with Republicans now in retreat and formerly radical positions like “abolish ICE” back in the political mainstream. To many Democrats, it would seem there is now little to lose from becoming a party wholly opposed to Trump’s immigration agenda.

Or is there?

The case for complexity

Looked at in a certain light, the present moment bears eerie similarities to Trump’s first term, when the Democratic Party, emboldened by the backlash to the president, sprinted left on immigration and cultural issues. But voters’ seeming openness to many ambitious liberal ideas evaporated almost immediately after Trump left office in 2021 — within months, positions that were toxic when he was their face, like building a border wall, became popular again.

The shadow of that era was long: Kamala Harris’s 2024 campaign was doomed in large part by her embrace of the most maximalist positions during Trump’s first term, including banning fracking, abolishing private health insurance, decriminalizing all border crossings, enacting the Green New Deal, and ending immigration detention (all positions she reversed during her campaign).

Right now, there’s some evidence that the party may be replicating that mistake. In recent months, polls have consistently identified a disconnect between Americans’ views of Trump’s handling of “immigration” and his handling of “border security.” In the past month alone, four national surveys found a significant difference in the president’s numbers on the issues.

The data points to an emerging complexity in Americans’ views on Trump’s record. To be sure, voters have long had complicated views on immigration — in the run-up to the 2024 election, surveys routinely found a majority of Americans saying they supported both deporting all illegal/undocumented immigrants and offering a path to citizenship to some. But the nuance has seemed to only deepen in Trump’s second term, with the median voter now supporting the president’s policies to prevent people from entering the country illegally while opposing his policies to remove those already here.

A Tuesday Siena College survey of New York State is a good example. The poll found a supermajority of residents, including a majority of Republican voters, supporting Hochul’s proposal to restrict immigration enforcement in locations like schools and churches. At the same time, a plurality of voters — in a deep blue state, remember — approved of Trump’s handling of “America’s border with Mexico” over the past year.

Siena College February 2026 survey

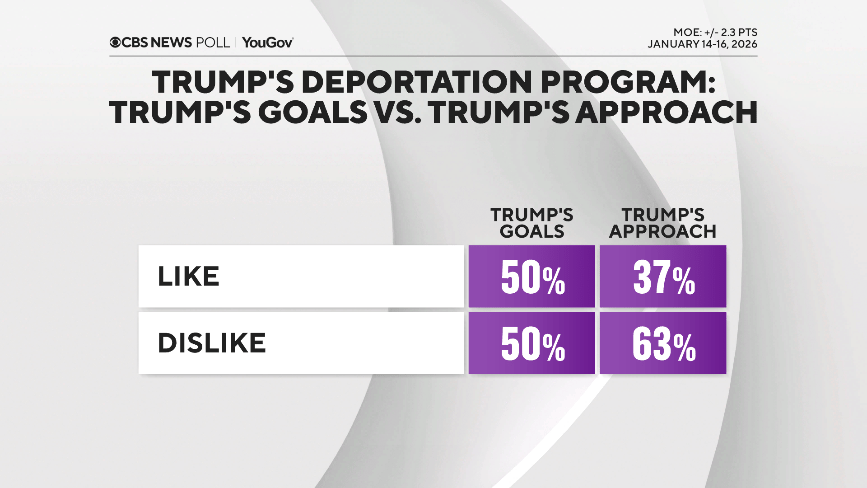

Another example was seen in a January CBS News poll. It found Americans deeply disapproving of Trump’s approach to deportation, but split exactly on the merits of Trump’s deportation goals — which is not merely a standard conservative effort but the "largest domestic deportation operation in American history.”

CBS News January 2026 survey

It’s not difficult to decipher where the support for Trump’s border policies comes from. President Biden oversaw the largest influx of immigration in U.S. history, a fact that still seems to weigh on the public’s mind.

The problem(s) with “abolish ICE”

No idea more neatly encapsulates the political tension than calls to abolish ICE, which first emerged back in 2018. The slogan, never popular to begin with, became nuclear-level toxic during Biden’s presidency, but has now returned to the Democratic mainstream. In fact, most polls find it more popular than ever, with several even showing a plurality of voters now favoring it.

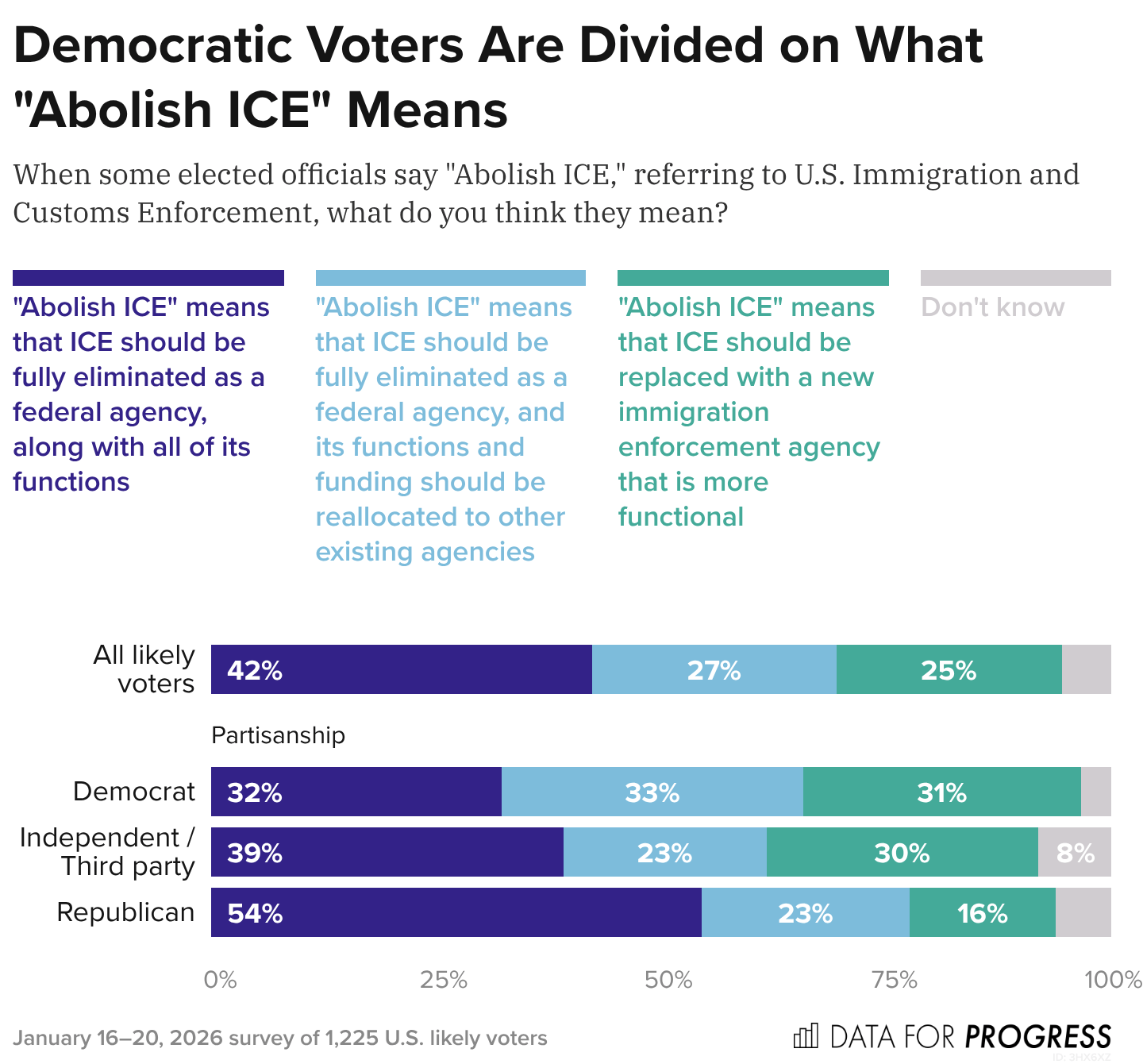

Setting the merits of abolishing the agency aside for a moment, the slogan itself has a number of problems — namely, that Americans don’t agree on what it means. In January, the left-leaning pollster Data for Progress found voters, including the Democrats most supportive of the slogan, split between considering it a call to end federal immigration enforcement or a call to end the current iteration of the agency.

In other words, the newfound popularity of the slogan itself has not brought with it a desire to end federal immigration enforcement altogether. Indeed, polls consistently show that Americans favor the existence of such efforts by enormous margins. To use just one example of literally dozens, a Pew Research survey released in December found that 82% of Americans believe at least some illegal/undocumented immigrants should be deported — a task that necessitates the existence of a federal immigration enforcement agency. One is certainly entitled to believe the country should cease all deportations, but they are in an extremely small minority.

This reality is what’s caused some Democrats to grow concerned the calls could haunt the party in the future, akin to “defund the police” in 2020. “Too often when voters hear you say ‘abolish ICE,’ they think that what you really want is to abolish federal immigration enforcement writ large,” Ahmad Ali, the Communications Director at Searchlight Institute, told me. Searchlight has been at the heart of efforts to discourage the calls, releasing several memos urging Democrats to avoid the language.

Many in the organized left reject the calls to caution, pointing to the agency’s legal and moral offenses in recent months. To them, there’s no ambiguity as to what “abolish ICE” does, or should, mean. “It means shutting down the agency and ensuring that that agency does not have funding to exist anymore,” said Usamah Andrabi, spokesperson for the progressive group Justice Democrats. “That’s what ‘abolishing ICE,’ ‘melt ICE,’ these things mean to us.”

On one level, the dynamic — progressives drawing clear moral lines and urging ambitious action, more moderate forces pitching strategy and long-term thinking — is nothing new in Democratic politics.

But the fear of a 2018-style overstep is not the only problem for the abolish slogan. If ICE disappeared tomorrow, an agency like Customs and Border Protection, which is already present in cities like Minneapolis, would still be at the president’s command (notably, Alex Pretti was killed by a CBP officer, not an ICE agent). For that matter, Trump has already used the National Guard to buttress deportation goals. Thus far, no one is calling for its abolition.

It’s here that those advocating the most literal interpretation of “abolition” — ending the agency without recreating it — have both their best and worst argument: that the existence of any immigration enforcement agency is going to provide Trump an opening to achieve his ends. This is true. But after the events of the past year, applying this standard consistently would necessitate the abolition of huge swaths of the federal government, from the FBI, FTC, and FCC to the entire Department of Justice, all of which have been deployed by the president for his personal political goals. As difficult as it may be to accept, the only way to actually prevent the president from abusing federal agencies was to prevent his return to the White House, a task Democrats failed at.

That’s left the party with few options — and helps explain the recent movement in governors’ mansions.

The case that this time is different

At the same time, there are real signs the country is in a different place than during Trump’s first term.

To begin with, polls show the public has warmed significantly to immigration overall: last summer, Gallup found 79% of Americans describing immigration as a “good thing” for the country, a record high. Voters’ concern with the issue overall has abated as well. In February 2024, the pollster found Americans felt immigration was the biggest problem facing the country. Its newest data finds economic issues are now top of mind.

Americans' views of ICE specifically are now decidedly more negative than at any time during Trump 1. In the summer of 2018, when outrage over family separation was making hawkish immigration policies deeply unpopular, Pew Research found the country split nearly evenly on its views of the agency, with 44% viewing it favorably and 47% unfavorably.

Now, Americans view the agency far more negatively than even then. Polls in recent weeks have found firm majorities viewing the agency unfavorably and supermajorities disapproving of its tactics.

The change is due in large part to a qualitative difference in the agency’s structure and purview. The ICE of 2026 boasts a budget almost triple the size of the ICE of Trump’s first term. It is now the best-funded law enforcement agency in the entire U.S. government, with an annual budget larger than 28 states. It has been tasked with running the most expansive deportation effort in the country’s history, a mission that has swept up dozens of American citizens. Conservative, Republican-appointed judges now regularly decry the agency for defying court orders and statutes. And it is now routine for ICE officers to be masked as they conduct their operations, which have killed two U.S. citizens in the past month.

Contrary to viral claims that this is what ICE has “always been,” this is not what the agency even was under Trump the first time — and Americans have noticed. Ultimately, the lessons of Trump’s first term may still apply, and at least some figures seem to be keeping them in mind. Hochul, for example, took pains to remind reporters that the state still cooperated on criminal immigration cases. Moore has recently emphasized his support for border security, telling The Press Box podcast last week, “Do we need to have a secure border? Absolutely, and we for a long period of time did not have that.”

In that sense, it may not be 2018 again. The party is more cautious, less insulated, and is facing an opponent who is using the federal government in a far different way than during his first term. But the lessons of last time may still apply.

Got feedback on today’s newsletter? Email me [email protected]