Eighteen years ago this month, Barack Obama made a casual comment to an editorial board. It foreshadowed the emerging problem for Donald Trump’s second term.

Sitting for an interview with the Reno Gazette-Journal, Obama reflected on the ability of some presidents to leave a lasting mark on the country’s political debates. "I think Ronald Reagan changed the trajectory of America in a way that Richard Nixon did not and in a way that Bill Clinton did not,” he said. “He put us on a fundamentally different path because the country was ready for it."

At the time, the comments became a bit of a headache for Obama. They ricocheted around the early Internet politisphere, becoming a weeks-long story. Hillary Clinton, eager for any inroad to Obama’s left, argued he was praising a conservative Republican to the detriment of Democratic presidents like her husband.

Nearly two decades later, though, almost everyone in politics agrees with the core point: a truly successful, transformational presidency is one that pushes both parties in the same direction, shifting the boundaries of debate as figures like Reagan or FDR did (While his own legacy, especially on economic issues, is complicated, Obama is arguably a good example of this on cultural issues: he oversaw Democrats’ transformation into an almost uniformly pro-choice and pro-LGBTQ party, and left the 2020s Republican Party is far less overtly anti-abortion, anti-gay, and anti-drug than it was in the 2000s).

By this metric, President Trump was, late into last year, well-positioned to meet the criteria, specifically on immigration. Throughout last year, the political landscape was littered with examples of the Democratic Party’s sprint to the center: dozens of congressional Democrats were voting for stricter border policies; liberal governors like Maura Healey were praising the president’s border enforcement policies; swing state governors like Katie Hobbs were signing executive orders to “secure the border”; and figures from Pete Buttigieg to Bernie Sanders to Hakeem Jeffries were using language that, as recently as 2024, would have gotten one exiled from polite liberal circles. An emerging consensus on immigration — more hawkish than at any time in decades — seemed to have been born.

Less than a month into 2026, that prospect looks almost entirely dead. As backlash mounts after the killing of Alex Pretti, Trump has seemingly squandered almost all the political capital he had amassed at the outset of his presidency. The result is a Democratic Party shifting left even quicker than it moved right, threatening his deportation agenda and potentially setting up even more dramatic clashes in the future. Here’s a rundown of the four things to know about the emerging new immigration landscape.

1. “Sanctuary” policies still exist — but they matter way less now.

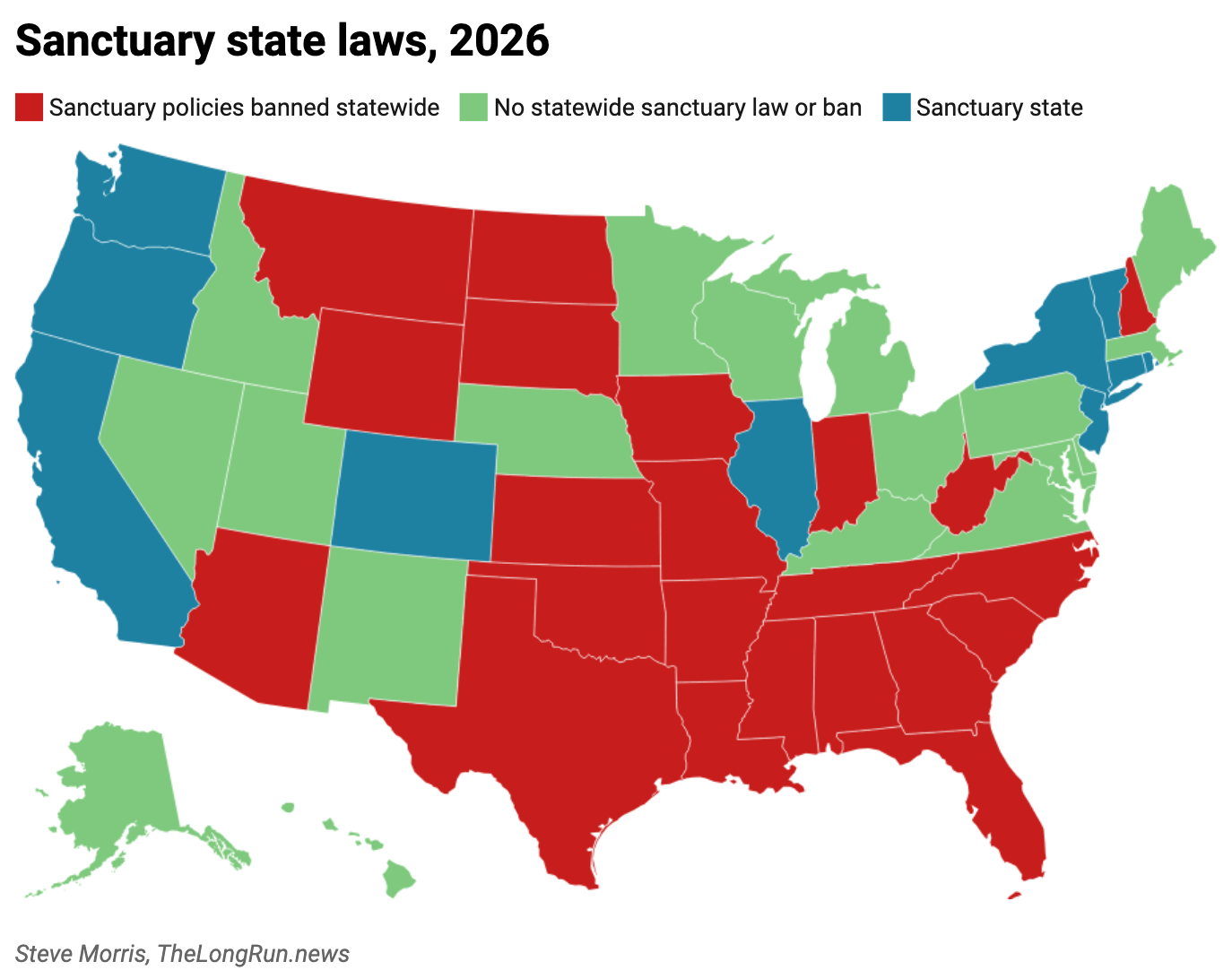

During the 2010s, “sanctuary” policies — generally defined as laws limiting cooperation between state or local police and federal immigration officials — were central to the immigration debate. The laws were largely limited to the most liberal areas of the country (the Obama administration was displeased by them, for example). But during Trump’s first presidency, sanctuary policies burst into the mainstream: the number of sanctuary states today is more than double what it stood in the Fall of 2016.

It’s worth noting that “sanctuary” laws are an imperfect and sometimes confusing label. The term has no official legal meaning, and it’s most often used by the most hawkish or anti-immigrant voices, who frequently have a very broad definition of the term (the anti-immigration Center for Immigration Studies lists ruby-red Utah as a sanctuary state, for example). True to modern form, states’ level of cooperation with federal immigration authorities is also more often a spectrum than a binary.

All of which is to say, the definition is difficult and imprecise. But there is generally some agreement about the states that meet the definition, and there is certainly no ambiguity regarding the states that have banned localities from adopting sanctuary policies. As is the case with so many other issues, cooperation with federal immigration enforcement is increasingly dividing along red-and-blue lines, with a supermajority now having some form of statewide law.

Sources: New York Times, Associated Press, DHS

Traditionally, sanctuary policies’ impact has been less about what ICE can do and more about where ICE chooses to do it. Studies have shown that ICE operations correlated directly with areas of the country that welcome their involvement. In other words, the chief effect of sanctuary policies has traditionally been their ability to keep ICE out altogether — with a limited budget and finite staffing, the agency chose to focus its efforts on cities and states where law enforcement was cooperative.

In the second Trump presidency, though, that dynamic has changed. The 2025 Republican reconciliation law effectively tripled ICE’s budget — providing it with up to $30 billion annually — making it the highest-funded law enforcement entity in the entire federal government. The agency is set to hire as many as 10,000 new agents, and has tens of billions more at its disposal for detention and enforcement efforts.

2. Trump’s deportation goals still require state and local cooperation.

Even as federal agents have more capacity than ever to operate independently, local cooperation has never been more crucial to Trump’s agenda. To understand why, it’s necessary to rewind a decade, when sanctuary policies were having an appreciable impact on deportation numbers. Over the course of Obama’s presidency, the number of deportations that came about through ICE arrests plummeted, largely because of the rise of sanctuary cities.

Source: Center for Migration Studies

At the same time, deportation numbers remained high over the course of Obama’s years in office because Customs and Border Protection continued to apprehend so many people at the border. Put simply, while ICE arrested fewer people in places like Denver or New York, CBP held steady in arresting people in places like the Rio Grande Valley.

For Obama, who largely focused his administration’s efforts on new arrivals and criminals, that mostly presented an annoyance. For Trump, it’s an existential problem for his deportation objectives.

To even come close to his goal of deporting millions of long-time residents, he needs ICE to be able to penetrate local communities across the country. As members of his administration have publicly acknowledged, programs like 287(g) agreements — partnerships that allow state and local officials to provide assistance to ICE and can essentially multiply ICE — are crucial to those efforts. And it’s here that Trump’s squandering of his opening matters so much.

There’s already evidence that the administration’s efforts are disproportionately concentrated in red states. According to the Deportation Data Project, nearly 40% of all ICE arrests in the first six months of 2025 occurred in Texas, Florida, and Georgia, with nearly a quarter coming from Texas alone. At a certain point, the Trump administration is going to max out in red states — and larger operations in blue states are going to become necessary to meet its targets.

3. Democrats are moving further and further from cooperation.

The administration has succeeded in ramping up 287(g) agreements. In 2024, there were fewer than 150 nationwide. Per DHS, that number now stands at 1,373. The problem is that a bigger and bigger chunk of the country is now opting out of them.

Last July, Delaware became the seventh state to outlaw the agreements statewide (four more states currently do not have any agreements, though they do not ban them). Collectively, the states comprise nearly 25% of the American population, and more may soon be on the way. In recent weeks, the Democratic leaders of the New York and Maryland state senates have endorsed plans to ban the agreements. The latter will present an especially notable test given that the state’s governor, Wes Moore, harbors national ambitions. Where he falls on the effort will say much about the party’s direction.

What comes next is unclear. As a New York Times analysis recently showed, the administration has responded to blue states’ resistance by stepping up “at-large” arrests (those conducted in a community rather than at jails or prisons).

Source: New York Times

As the administration itself acknowledges, these are often the most chaotic and disruptive operations, the kind the administration has been mounting in Minnesota. There’s a real chance that the future could well hold more of them.

4. For now, abolition is a trickle, not a stampede.

The politics of ICE are becoming deja vu for some Democrats, who are watching some in the party return to the 2018-era call for the agency’s abolition. That stance was unpopular during Trump’s first term and became politically radioactive after he left office. There is, however, some evidence that the agency’s current iteration has changed Americans’ minds. The polling firm Civiqs, which has been tracking the question for years, now finds the idea still underwater but more popular than ever.

Source: Civiqs

So far, though, explicit calls for abolition, which have spread among members of the House of Representatives, have not reached the Democratic Senate caucus, governors’ mansions, or pool of 2028 contenders. The closest anyone has come is Illinois’s JB Pritzker, who called for “abolishing Trump’s ICE,” a line with enough space to make it almost meaningless. One Democratic strategist, who’s involved in efforts to dissuade the party from repeating “abolish ICE” messaging, said they expect 2028 contenders to continue to avoid the stance, though events like the Minnesota deaths are a significant variable.

Wherever the party lands on messaging, though, it seems the larger trajectory is set. A year into his second term, Trump is, by any reasonable metric, nowhere near close to his stated deportation goals. He has, however, destroyed the bipartisan consensus that briefly came into view after the 2024 election. For his agenda, that’s bad news. For his legacy, it could be even worse.

Got feedback on today’s newsletter? Email me [email protected]